By Courtney Lott –

Our God is a very big God. So big and so creative that a single human never could bear his image perfectly. In his vastness, he uses male and female, black and white, smart and simple, single and married to paint as full a picture as possible of his broad and unsearchable character. In One Blood, Dr. John M. Perkins weaves this truth together with grace and humility, wisdom, and love. He celebrates our ethnic diversity and confronts the sin of racism with both seriousness and gentleness, all the while keeping the gospel of Jesus front and center.

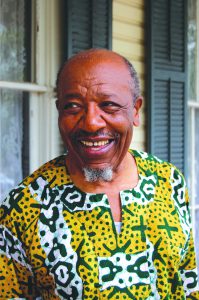

Perkins is a legendary civil rights activist, author, and an evangelical statesman. He is the founder of the famed Voice of Calvary Bible Institute, the Christian Community Development Association, and Harambee Ministries.

Perkins deftly frames his appeal by drawing from scripture. We are ultimately one race, one bright and shining reflection of the Godhead. However, in order to justify slavery and subsequent racial structures, we did some illogical leapfrogging. Though steeped in the idea that all individuals are created equal, the slave’s dignity was downplayed in the worst possible sense. This is where the social construction of race came into play.

“[T]here had to be distinctions made between normal folks and this new breed of people that would be treated like animals,” Perkins writes. “The truth is that there is no black race – and there is no white race. So the idea of ‘racial reconciliation’ is a false idea. It’s a lie. It implies that there is more than one race. This is absolutely false. God created only one race – the human race.”

One blood, one race of people who, in all their diversity, produce a more complete picture of the godhead. When I first began to learn about ethnic reconciliation (a phrase Perkins considers more accurate than racial reconciliation), the sheer idea overwhelmed me. But in One Blood, Perkins lays out practical steps and devotes an entire chapter to each.

The Measuring Line. Perkins begins with a measuring line, a standard for what the church ought to look like. Citing the great congregation from every tribe, tongue, and nation as seen by John in Revelation 7, he describes experiencing a “prelude to heaven” while visiting Bridgeway Community Church, a multiethnic congregation in Columbia, Maryland.

For Perkins, Bridgeway was a “picture of the oneness and the diversity of the body of Christ … a physical representation of it,” he writes. “And it was glorious! The melting of the cultures was beautiful; the blend of ethnicities was evident across the ranks of the leadership and the membership. And the music carried me away. I saw echoes of the great congregation that will stand around the throne shouting ‘Holy, Holy, Holy! Worthy is the lamb!’”

This particular church modeled biblical, ethnic reconciliation, a vital part of the gospel, according to Perkins. Though Christ came primarily to restore our relationship with God the Father, he also came to restore our relationships with each other. Neglecting this aspect of the kingdom is a grave mistake and does a disservice to Christ’s work.

“This vision for unity is borne on the wings of the good news of the gospel. It’s good news and it’s for all the people,” writes  Perkins. “It’s the good news that Luke proclaimed, ‘Do not be afraid; for behold, I bring you good news of great joy which will be for all the people; for today in the city of David there has been born for you a Savior, who is Christ the Lord!’ (Luke 2:10-11). This supernatural announcement is one of the most compelling signs that God intends for His gospel to reach all nations and cultures.”

Perkins. “It’s the good news that Luke proclaimed, ‘Do not be afraid; for behold, I bring you good news of great joy which will be for all the people; for today in the city of David there has been born for you a Savior, who is Christ the Lord!’ (Luke 2:10-11). This supernatural announcement is one of the most compelling signs that God intends for His gospel to reach all nations and cultures.”

Angels announced this good news to shepherds first. As social outcasts and caretakers of sheep, they understood their need for a sacrificial lamb, understood what it felt like to be on the margins. Never meant to be an exclusive club, Perkins reminds us that the kingdom of heaven is for all peoples, including those we might be biased against. This message the angels brought was one of hope and reconciliation, both with God and our fellow man.

Looking Back on History. Though the United States started with the idea of equality for all, we quickly got off track, Perkins says. In order to justify slavery, many used the social construction of race, focusing on the ways in which we are different. However, a close look at what scripture has to say about humanity reveals we are far more alike than our physical attributes might indicate. Perkins sites the creation of Adam in his argument that we are, in fact, one race.

“I understood from the Genesis account God’s intimate interaction with Adam when he created him, breathing into him the very breath of life,” writes Perkins. “I understood that God was literally breathing dignity and character into this man Adam … From this one man, Adam, who was created in the very image of God, the entire human race sprang.”

Both scripture and science have been abused in order to perpetuate race theory, a concept that is foundational to racism and countless other ills. These wrongs run deep and at times appear insurmountable. There is, however, hope and Perkins has experienced it personally. After experiencing severe abuse – civil rights arrest and brutality – in his native Mississippi, he never thought he would be able to return to his hometown and the people who wronged him.

Then he met Jesus. “I left Mississippi with hate in my heart,” Perkins writes. “God brought me back with a heart that was overflowing with his love. I had been reconciled to Christ, and he prepared me to return to Mississippi to be reconciled to my white brothers and sisters.”

The love of Christ, the “ultimate reconciler,” is our only hope when it comes to achieving the unity we are called to. This is the foundation upon which Perkins builds the rest of the book. Reconciliation that works is based on the gospel.

One aspect of the gospel we often overlook is the call to corporate lament. As those brought up on the idea of individualism and the American dream, this heavy concept of corporately mourning can be uncomfortable, if not painful. However, if we are to be true to the Scriptures we know and love, we must face the reality that Christ calls us to lament. Though looking back on past shame is difficult, confronting our history is often the only way to move forward.

“Scripture was never intended to be used solely for individual application,” Perkins writes. “It was meant for the community of believers. The psalms of lament were meant to be tools in the community worship experience to bring the worshipers into the presence of our God. The lament is his gift to us, his church.”

Confession goes hand in hand with lament. It is in this section that Perkins explains the term “white privilege”— a highly divisive and potentially polarizing term — in a helpful way. Many white Christians might need to confess denying that racism exists and that we benefit from our skin color, he writes. As this is difficult to address without offending, Perkins draws a parallel to the privilege of being a citizen of the United States.

“Through no fault or responsibility of our own, most of us were born in the United States of America,” he writes. “Though poverty does exist in America it exists at a level far above the level of poverty in a Third World country. This could be termed ‘American privilege.’ We are afforded certain advantages just because we live in America. It’s not something that we should feel guilty about, but it is important for us to be aware of these realities … In a similar way being white in this country affords certain advantages that can be easily overlooked.”

We have tried to create God in our own image, says Perkins. Whatever makes us the most comfortable — liberal, conservative, Western, white — we remake Jesus into something that he is not: safe and sanitary. Fear drives us to this mistake and, according to Perkins, this is something else we must confess as sin. White individuals fear losing their power and status, black individuals fear the endless hard work that often doesn’t seem to bear fruit.

But God. Perkins’ refrain is always “but God.” But God’s word speaks into our fears and calls us to the perfect love that casts out all fear. God’s love can empower us to be uncomfortable and reach across the aisle, extending our hearts to one another. It also grants us the power to forgive in a way the world will sit up and notice.

As a profound example of this, Perkins sites the way the congregants of Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, reacted to Dylann Roof, the young white supremacist who opened fire on a Bible study there.

“At Dylann Roof’s bond hearing, the relatives of the victims stood to address him,” Perkins writes. “‘I forgive you.’ ‘I forgive you.’ ‘I forgive you.’ These three words were spoken again and again as the family members of the Charleston church victims spoke to the accused. It was clear that they were struggling with deep emotion and grief. Yet they chose to forgive rather than to hate … many of them saying that they were praying for his soul. The nation watched, spellbound.”

This church’s example was an incredible witness to the world of just how powerful God’s love is. Forgiveness is a painfully difficult thing. It means letting go of resentment for a deep wrong others have committed against you or your loved ones. This is only possible through the power of the Holy Spirit who inhabits the heart of every believer, Perkins writes, and even with this power, it is still no easy path.

The Weapon of Our Warfare. Throughout One Blood, Perkins constantly models prayer, a practice he calls the weapon of our warfare. He ends each chapter with a cry to the Lord based on the subject he has written on, guiding the reader on a profound and grace-filled journey through a difficult topic. Pastoral in his counsel, he offers practical topics to help guide us in our appeals to the Holy Spirit for reconciliation.

Moreover, Perkins points to numerous examples of pastors and churches that have sought this kind of reconciliation. Motivated by the love of Christ, these men and women have developed more diverse congregations in their communities and strived to better image the great multitude from Revelation.

“It’s going to take intentionally multiethnic and multicultural churches to bust through the chaos and confusion of the present moment and redirect our gaze to the revolutionary gospel of reconciliation,” Perkins writes. “I really believe that each of our souls yearn for this vision. We want it. We know in our heart of hearts that it is right.”

Perkins. “It’s the good news that Luke proclaimed, ‘Do not be afraid; for behold, I bring you good news of great joy which will be for all the people; for today in the city of David there has been born for you a Savior, who is Christ the Lord!’ (Luke 2:10-11). This supernatural announcement is one of the most compelling signs that God intends for His gospel to reach all nations and cultures.”

Perkins. “It’s the good news that Luke proclaimed, ‘Do not be afraid; for behold, I bring you good news of great joy which will be for all the people; for today in the city of David there has been born for you a Savior, who is Christ the Lord!’ (Luke 2:10-11). This supernatural announcement is one of the most compelling signs that God intends for His gospel to reach all nations and cultures.”

As a poetic artist, Lecrae makes a distinction between a “Pastor Rapper” and that of a “lamenter” – a passionate expression of grief or sorrow that is an outgrowth of his youth and the abandonment he felt. When he was free from trying to preach like a “Pastor Rapper,” Lecrae felt the words and rhythms flow when he allowed himself to be vulnerable and honest about his own battles.

As a poetic artist, Lecrae makes a distinction between a “Pastor Rapper” and that of a “lamenter” – a passionate expression of grief or sorrow that is an outgrowth of his youth and the abandonment he felt. When he was free from trying to preach like a “Pastor Rapper,” Lecrae felt the words and rhythms flow when he allowed himself to be vulnerable and honest about his own battles.

“Anyone who knows my story would expect this book to ooze with justice issues. After all, the pain caused by injustice has motivated me to spend a lifetime working for social change on behalf of widows, prisoners, the poor, and anyone who struggles,” writes Perkins, the civil rights veteran who has led the Voice of Calvary Ministries in Jackson, Mississippi, since 1975. “So how did someone who has experienced the anguish of poverty, racism, and oppression end up wanting to write a book about love as his climactic message? Good question… I’ve come to understand that true justice is wrapped up in love. God loves justice and wants His people to seek justice (Psalms 11 and Micah 6:8). But I’ve come to understand that true justice is wrapped up in love. The old-time preacher and prophet A.W. Tozer had a way of making the most profound truths simple and palatable. He once said, ‘God is love, and just as God is love, God is justice.’ That’s it! God’s love and justice come together in the redemptive work of Jesus Christ, and we can’t be about one and not the other. They’re inextricably connected.”

“Anyone who knows my story would expect this book to ooze with justice issues. After all, the pain caused by injustice has motivated me to spend a lifetime working for social change on behalf of widows, prisoners, the poor, and anyone who struggles,” writes Perkins, the civil rights veteran who has led the Voice of Calvary Ministries in Jackson, Mississippi, since 1975. “So how did someone who has experienced the anguish of poverty, racism, and oppression end up wanting to write a book about love as his climactic message? Good question… I’ve come to understand that true justice is wrapped up in love. God loves justice and wants His people to seek justice (Psalms 11 and Micah 6:8). But I’ve come to understand that true justice is wrapped up in love. The old-time preacher and prophet A.W. Tozer had a way of making the most profound truths simple and palatable. He once said, ‘God is love, and just as God is love, God is justice.’ That’s it! God’s love and justice come together in the redemptive work of Jesus Christ, and we can’t be about one and not the other. They’re inextricably connected.”