|

“But at the beginning of creation God ‘made them male and female.’ ‘For this reason a man will leave his father and mother and be united to his wife, and the two will become one flesh.’ So they are no longer two, but one flesh” (Mark 10:6-8).

What a beautiful and frightening thing marriage is. Two souls on a journey, joining to carry each other’s burdens, to know one another deeply, to image the relationship between Christ and the church in a unique way, and to be fruitful and multiply. It’s fitting that weddings are celebrations, that family and friends gather before God to rejoice in a covenantal relationship, the creation of a new, single flesh.

As the bride walks down the aisle, resplendent in white, we are reminded of John’s description of Jerusalem in Revelation 21 “coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride beautifully dressed for her husband.” We are reminded of how Christ sacrificed himself in order to clothe the church for her wedding day. We clap, we sing, we dance, we cry.

Most of these tears are free and full of happiness. Yet some are tears of longing, tears of fading hope, of loneliness. Torn between joy for friends and mourning for the feeling of being slightly displaced, these are the tears of the single, the divorced, the same sex attracted.

The Single. “We just need to get you married.”

I never quite know how to respond to such statements about my relationship status. Often thrown about with nonchalance, I don’t doubt the purveyors of such declarations mean well. They listen to my story, hear my words, and are sympathetic. Yet their solution is often the same: “We just need to get you married” as if this is as simple as finding a new pair of shoes, as if this always solves the problem of loneliness.

Within our culture, both Christian and secular, romantic relationships are held in high esteem. The secular culture snickers at virginity, slapping on the label of prude, while Christian culture assumes older singles are immature or too picky.

In movies, participation in one is often portrayed as a sign that the main character – once a stagnant workaholic/sad social pariah – has now arrived at life’s deepest meaning and will prance off into the sunset to be forever happy and contented. Phrases like “old maid,” “biological clock,” or “ending up alone” are hung around the necks of singles past a certain age.

More frustrating still, as our younger counterparts join the ranks of the married, we start to age out of our “allotted places” within the church. In my experience, most “singles ministries” are occupied by college students or recent grads. Anyone beyond this is semi-unwelcome, considered at least somewhat awkward, and makes everyone uncomfortable. I know, because when I was just out of college, I felt the same way about older singles. The plank in my own eye is a big one.

Who Sinned? As for our married counterparts, a great many (at least in the south) married young, right out of college or even prior to walking across the stage. Their claims to understanding our singleness ring somewhat hollow and their declarations that we simply need to be “content in the Lord” before he will bring us the right person sting.

There is a sort of unspoken assumption made based on this idea. Like the barren women in ancient Israel or the blind man in Jesus’ day, it seems as if the single is often viewed as an unfortunate misfit.

And we singles are not alone in this category. Many in the church bear a particularly difficult burden that often brings with it a painful dose of shame. The divorced often feel that, like Hawthorne’s heroine, they wear a massive scarlet letter “D” wherever they go.

Communicating their experiences is difficult and uncomfortable. One or both separated spouses often must leave their shared church family after the relationship is broken, thus causing even more pain. A joined life is rent in two and the dynamics change. Like the single, the divorced can feel awkward in situations where most people are couples.

The Outcasts. Oddly enough, the writings of celibate same sex attracted Christians reflect my heart and understand my pain far better than anyone else. Writers like Wesley Hill, assistant professor of New Testament at Trinity School for Ministry in Ambridge, Pennsylvania, and editor of the website Spiritual Friendship, speak of building community apart from romantic relationships, of mourning a certain kind of companionship you’ll likely never have. Spiritual Friendship, an online community of Christians who are primarily same sex attracted, embraces “the traditional understanding that God created us male and female, and that his plan for sexual intimacy is only properly fulfilled in the union of husband and wife in marriage.”

However, these writers also desire to change the discussion surrounding homosexuality. Through their blog posts, the contributors speak on “celibacy, friendship, the value of the single life, and similar topics.” Rather than relying on platitudes or the mistaken idea that God’s goal for all of us is marriage, this community laments their situation and challenges the church in a unique way.

I need them. The church needs them.

The Inner Circle. But I’m often too quick to dismiss the trials and tribulations of the married. Sometimes I get irritated when I hear their complaints. At least you’re not alone, I think. At least you’ll be leaving a legacy in your offspring. Yet when I take a moment to listen, to empathize, I realize they have lessons for me. When they tell me they are lonely in marriage, when they admit their children are driving them crazy, or even worse, when they confess to feeling trapped and embittered, I am reminded marriage is never happily-ever-after. It is not the end all be all, and it will not satisfy my deepest longings, for it is not the purpose of the Kingdom of God. I know this in theory, but I don’t really believe it, not functionally.

We all need each other. The married stay-at-home mom needs the single admin assistant. The single bachelor needs the father of 2.5 kids. The barren woman needs the mom with the child who has autism. The ultra conservative pastor needs the same sex attracted Christian columnist. Our different perspectives, our different paths, offer lessons none of us can learn on our own. Rather than dividing ourselves and telling one another “you can’t understand me,” when we share our stories, our tears, our joys, we unite ourselves in a marriage like covenant.

Within the church, no one should ever be truly alone.

This may all seem obvious. We’re the church. Christ died to make her his body. But we don’t always act like we believe this.

When people don’t follow our cultural norms, they make us uncomfortable and we do what we can to “fix the problem.” We try to get the single married, change someone’s sexual orientation, find a way to quiet the distracting child, or give the barren woman a platitude. What if we mourned with each other instead? What if, rather than trying to make ourselves comfortable by changing another person’s situation, we listened a little better?

I need you. You need me. That’s part of how we reflect the Trinity. We’re made to be relational, even when relationships shove us out of our comfort zones, especially when they shove us out of our comfort zones. Life is hard enough without creating barriers. We’re meant to carry one another’s burdens, to mourn and lament the effects of sin in the world, to love and challenge each other to walk with the Lord.

We need each other.

As a poetic artist, Lecrae makes a distinction between a “Pastor Rapper” and that of a “lamenter” – a passionate expression of grief or sorrow that is an outgrowth of his youth and the abandonment he felt. When he was free from trying to preach like a “Pastor Rapper,” Lecrae felt the words and rhythms flow when he allowed himself to be vulnerable and honest about his own battles.

As a poetic artist, Lecrae makes a distinction between a “Pastor Rapper” and that of a “lamenter” – a passionate expression of grief or sorrow that is an outgrowth of his youth and the abandonment he felt. When he was free from trying to preach like a “Pastor Rapper,” Lecrae felt the words and rhythms flow when he allowed himself to be vulnerable and honest about his own battles.

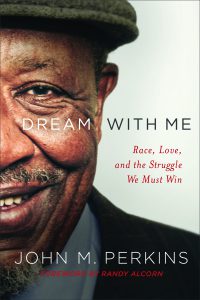

“Anyone who knows my story would expect this book to ooze with justice issues. After all, the pain caused by injustice has motivated me to spend a lifetime working for social change on behalf of widows, prisoners, the poor, and anyone who struggles,” writes Perkins, the civil rights veteran who has led the Voice of Calvary Ministries in Jackson, Mississippi, since 1975. “So how did someone who has experienced the anguish of poverty, racism, and oppression end up wanting to write a book about love as his climactic message? Good question… I’ve come to understand that true justice is wrapped up in love. God loves justice and wants His people to seek justice (Psalms 11 and Micah 6:8). But I’ve come to understand that true justice is wrapped up in love. The old-time preacher and prophet A.W. Tozer had a way of making the most profound truths simple and palatable. He once said, ‘God is love, and just as God is love, God is justice.’ That’s it! God’s love and justice come together in the redemptive work of Jesus Christ, and we can’t be about one and not the other. They’re inextricably connected.”

“Anyone who knows my story would expect this book to ooze with justice issues. After all, the pain caused by injustice has motivated me to spend a lifetime working for social change on behalf of widows, prisoners, the poor, and anyone who struggles,” writes Perkins, the civil rights veteran who has led the Voice of Calvary Ministries in Jackson, Mississippi, since 1975. “So how did someone who has experienced the anguish of poverty, racism, and oppression end up wanting to write a book about love as his climactic message? Good question… I’ve come to understand that true justice is wrapped up in love. God loves justice and wants His people to seek justice (Psalms 11 and Micah 6:8). But I’ve come to understand that true justice is wrapped up in love. The old-time preacher and prophet A.W. Tozer had a way of making the most profound truths simple and palatable. He once said, ‘God is love, and just as God is love, God is justice.’ That’s it! God’s love and justice come together in the redemptive work of Jesus Christ, and we can’t be about one and not the other. They’re inextricably connected.”